HOME

TOPICS

ABOUT ME

Your brain hardly ever second-guesses itself.

Starting our fourth decade: Al Fasoldt's reviews and commentaries, continuously online for 30 years

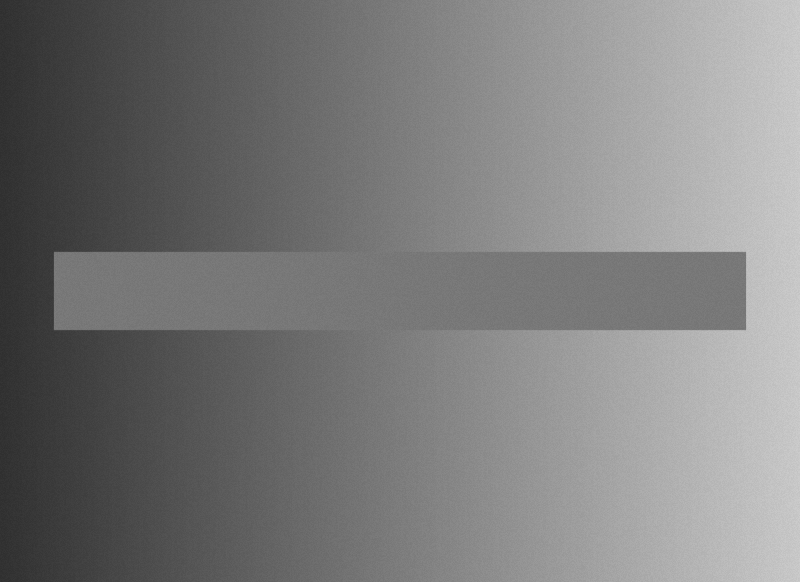

The gray bar seems to be lighter in some areas than in others. But is your brain playing a trick on you?

Why seeing isn't always believing

Aoril 27, 2014

By Al Fasoldt

Copyright © 2014, Al Fasoldt

Copyright © 2014, The Post-Standard

I wrote recently about JPEGMini, which squeezes photo files down to their tiniest possible sizes. It does this even though it chops pictures up and tosses out half the good stuff.

I also wrote about how carefully I looked for signs that my pictures had gone through a byte grinder after JPEGMini had done its dirty deeds. It was almost impossible to see any differences without zooming in on individual parts of the pictures, something most people would never do anyway. (Read the original report at www.technofileonline.com/texts/tec040614.html.)

How is this possible? Stripping a photo of all that data -- literally removing pixels by the thousands, left and right -- should make a mess.

But it doesn't.

The fact that JPEGMini gets away with this is simply a sign that we sometimes don't see what's really there. We can't blame our eyes -- after all, they're doing the best they can -- but we can hold something else responsible: Our brain.

The human brain tries its best to make sense of the images our eyes send its way. Our eyes don't think. Our brain does. So if a rock is falling off a cliff and we're underneath it, our eyes simply see an object getting larger and larger. Our brain sees an object getting closer and closer, and it signals our legs to start running.

Your brain acts very quickly. It has to make decisions in an instant. So it hardly ever second-guesses itself. (Just as you might have suspected, even when you think about decisions for a long time, you almost always choose the first thing you thought of.)

No second guessing means accepting the way things appear. Or, more to the point of JPEGs, the way things seem to appear. All that stuff missing from a photo after it's been JPEG-ized just seems to be there. Our brains are especially fooled by objects that are next to each other; one influences how we see the other.

For proof, look at the graphic accompanying today's column. There's a gray bar on top of a gray rectangle. Your brain sees the gray bar as being lighter in some areas than in others.

But it's not. It's the same shade of gray from left to right. Cover up the area above and below the gray bar and look again.

Fooling your brain like this is just one of the ways JPEGs work. There are others. We'll look at those another time.